Lead Contamination

Lead is a toxic metal that can cause severe health problems, especially in children. Fortunately, you can take steps to reduce your family’s risk of exposure. Getting your home checked for potential lead hazards is a good first step.

Lead is widely used in everything from car batteries to ammunition to protective X-ray aprons. But before people realized how dangerous lead can be, it was used in many more products.

Much of the lead we encounter in the environment today comes from leaded gasoline sold throughout most of the mid-20th century. The federal government began phasing out leaded gas in the 1970s and banned it completely in 1996. But remnants of lead emissions from gasoline and other industrial sources that have settled from the air onto soil and dust remain a risk and can still be accidentally ingested.

Other common sources of environmental lead exposure include lead-based paint and lead pipes.

There is no safe level of lead exposure. Lead that’s inhaled or ingested will accumulate in the body and cause severe health consequences. Children are especially susceptible to lead poisoning and can end up with permanent damage.

Fortunately, lead poisoning is a preventable environmental health problem, and there are important steps you can take to reduce your risks and make your home safe.

Where Is Lead Found?

Lead is everywhere, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. It’s in our air, soil, water and even our homes. And while some of the major historical sources of lead contamination — such as leaded gasoline and lead-based paints — have been banned for decades, remnants of their use remain.

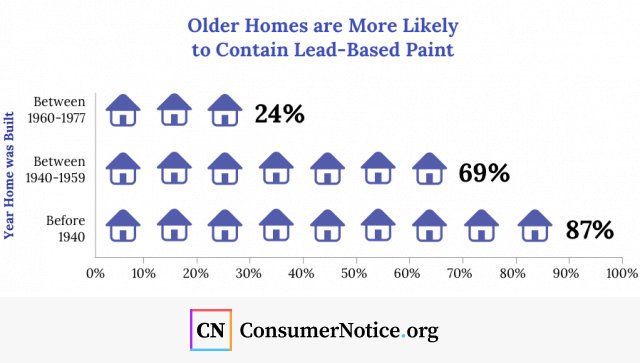

Lead chips and dust from old paint are one of the leading causes of lead exposure among children in the United States. In 1978, the Consumer Product Safety Commission banned the use of lead in household paint, but it’s still present in many old houses and buildings. Houses built prior to 1950 are even more likely to contain lead paint.

If the paint in your home is in good condition and intact, it’s less likely to pose a hazard. But paint that’s chipped or peeling can be ingested or inhaled. Older toys, furniture and playground equipment may also contain lead paint. Home renovations that require sanding, cutting and demolition can disturb lead-based paint and create dangerous lead dust.

Other sources of lead exposure include:

- Contaminated soil

- Contaminated drinking water

- Tableware, including poorly glazed ceramic dishes and pottery, leaded crystal, metal powder and brass dishware

- Home remedies/folk remedies

- Toy jewelry

- Imported toys

- Artificial turf

- Imported canned foods

- Contaminated cosmetics

- Contaminated candy imported from Mexico

Certain jobs — such as demolition, painting, remodeling, construction and battery recycling — can expose workers to lead. Workers who encounter lead on the job can accidentally bring lead dust home on their clothing and endanger family members.

Certain recreational activities can also raise a person’s risk of lead exposure. Risky hobbies may include: welding; glazing or making pottery; repairing cars or boats; refinishing furniture; remodeling homes; painting; and target shooting.

Lead Pipes and Water

Lead pipes can contaminate drinking water. Although lead plumbing pipes were banned in 1986, up to 10 million homes across the country still get their water through lead pipes, according to the Environmental Defense Fund.

The biggest danger occurs when acidic water flows through the pipes. Acidic water is corrosive and can leach lead and other dangerous metals from the plumbing, resulting in water contamination.

Water utility systems are supposed to treat their water to make it non-corrosive, but that doesn’t always happen. In fact, the failure to do so is what sparked the notorious water crisis in Flint, Michigan.

Harmful Effects of Lead Exposure

Lead is toxic, and there is no safe level of exposure. Because it harms numerous body systems, it can cause a range of ill effects.

Effects may not be noticeable right away. Signs and symptoms may not show up until significant amounts of the toxic metal have accumulated in the body.

Acute lead poisoning, which occurs with short-term exposure to high levels of the metal, may cause the following symptoms:

- Headaches

- Abdominal pain

- Constipation

- Fatigue

- Weakness

- Irritability

- Decreased appetite

- Memory problems

- Joint and muscle pain

- Tingling or pain in the hands or feet

Because the symptoms are non-specific, lead-poisoning can easily be mistaken for other illnesses and go undiagnosed. Over time, lead exposure can lead to high blood pressure, heart disease and fertility problems. It can also cause anemia, kidney damage and brain damage. You can even die from lead poisoning.

Lead enters the body in one of two ways. It’s either inhaled or ingested. Once it enters the blood stream, it’s deposited in various organs, including the brain, heart, lungs, kidneys, liver and bones.

Approximately 95 percent of the lead an adult ingests will end up in their bones and teeth. But it doesn’t necessarily remain there. During times of stress, including pregnancy and during breastfeeding, lead can be reabsorbed into the bloodstream. Lead is also released from bones into the bloodstream when women are in menopause.

Effects on Children

Elevated levels of lead can harm anyone, but children and babies are particularly susceptible to the dangers. Young children can absorb four to five times as much lead as an adult does, making them especially vulnerable to lead poisoning. Children under the age of 6 are the most at risk.

Children who are exposed to lead can develop:

- Brain and nervous system damage

- Slowed growth and development

- Behavioral problems, learning difficulties and lower IQs

- Hearing and speech difficulties

Young children naturally have a higher risk of lead poisoning than adults because they tend to put things in their mouths. Children with pica, a disorder that causes them to compulsively eat non-food items, are particularly vulnerable. It’s not unusual for them to peel and pick paint chips off walls or furniture and eat them.

Other signs and symptoms of childhood lead poisoning may include:

- Poor appetite

- Weight loss

- Fatigue and irritability

- Belly pain

- Vomiting

- Constipation

- Seizures, coma and death

Children who are undernourished will absorb more lead than those who are fed a well-balanced diet. That’s just one of the reasons impoverished children face a higher risk of lead poisoning. They’re also more likely to live in older rental units that still contain lead paint.

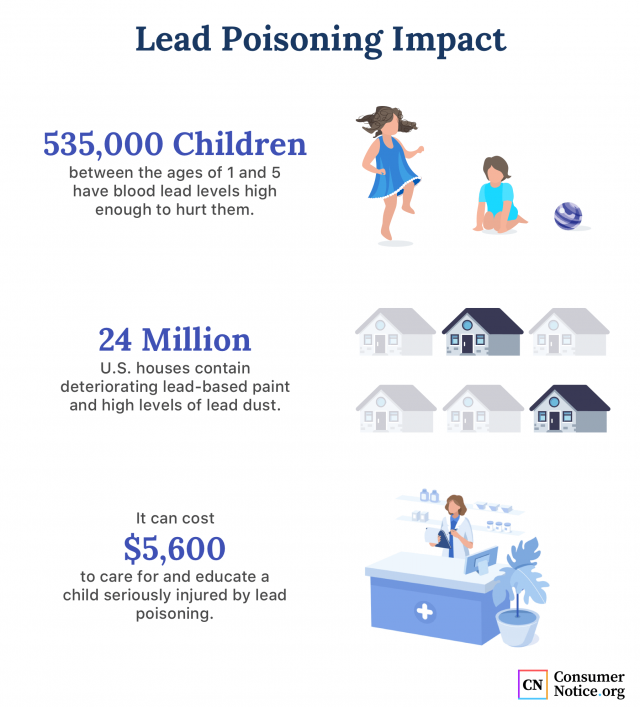

Although lead poisoning is preventable, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 500,000 children under the age of 5 have blood lead levels above 5 micrograms per deciliter, which is considered the level of concern.

A 2008 study in the journal of Environmental Health Perspectives found that as lead blood levels in young children rise from 5 mcg to 10 mcg/dcl, the children’s IQs decline by about five points. When blood levels increase to 45 micrograms per deciliter, children should receive a treatment known as chelation therapy, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. Chelation drugs bind with the lead to help the body excrete it.

Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

Lead poses serious risks to pregnant women. It easily crosses from the mother’s bloodstream into the placenta, and lead has been detected in the brains of developing babies at the end of the first trimester, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Lead exposure can lead to miscarriages, stillbirths and premature births. Newborns who’ve been exposed to lead may be underweight and may grow more slowly. Pregnant women with risk factors should get their lead blood levels tested.

According to the National Capital Poison Center, risk factors for expectant mothers include:

- Recently living in a country with high levels of environmental lead

- Living or working near a source of lead

- Practicing a hobby that involves the use of lead

- Using tainted tableware, cosmetics or other items

- Renovating a home that contains lead-based paint

- Having a history of lead exposure or living with someone with high lead levels

Lead can also be passed from mothers to babies through breast milk. The CDC recommends that women with blood lead levels under 40 mcg/dL still breastfeed, but that their infants be closely monitored to ensure that the baby’s blood levels remain under 5 mcg/dL.

How to Protect Your Family

While there are some treatments that can help remove lead from the body, prevention is the best medicine.

There are many steps you can take to reduce potential lead exposure.

- Don’t let your children put their mouths on windowsills, toys or other painted surfaces.

- Don’t allow your child to play in bare soil.

- Don’t allow your baby to chew on keys, as they sometimes contain small amounts of lead.

- If you live in a home built before 1978, get it inspected for lead contamination.

- If you have lead-based paint in your home, use a certified contractor to repair or replace any chipped or cracked paint.

- Cover any chipped or peeling paint with duct tape until it can be repaired or removed.

- Avoid imported toys, jewelry, candy, spices and other products that have been found to contain lead. Check the Consumer Product Safety Commission’s website for product recalls.

- Avoid using folk medicines or remedies that may contain lead.

- Don’t eat food that has been canned outside of the United States.

- Wash children’s hands and toys frequently. Both can become contaminated with dust, which is a common source of lead.

- Regularly wet-wipe windowsills and mop floors to eliminate household dust.

- Regularly wet-wipe windowsills and mop floors to eliminate household dust. Feed your family a healthy diet with adequate calcium and iron. This can reduce lead absorption.

- Filter your water or run cold tap water for a few minutes before using it.

- Because hot water increases lead levels, only use cold tap water for cooking or drinking.

- drinking. If you work with lead, leave contaminated clothing in your work area and shower as soon as you get home.

Screening is an important part of preventing lead poisoning. Talk to your doctor to find out if your child is at risk and should be screened. Likewise, you may want to have your house or tap water tested for lead if you are concerned about lead contamination.

To learn more about protecting your family from lead hazards, read this in-depth guide from the EPA.

30 Cited Research Articles

Consumernotice.org adheres to the highest ethical standards for content production and references only credible sources of information, including government reports, interviews with experts, highly regarded nonprofit organizations, peer-reviewed journals, court records and academic organizations. You can learn more about our dedication to relevance, accuracy and transparency by reading our editorial policy.

- Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry. (2017, June 12). Lead Toxicity: What is the Biological Fate of Lead in the Body? Retrieved from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.asp?csem=34&po=9

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2017, August 30). Blood Lead Levels in Children: What Parents Need to Know. Retrieved from https://www.healthychildren.org/English/safety-prevention/all-around/Pages/Blood-Lead-Levels-in-Children-What-Parents-Need-to-Know.aspx

- California Poison Control System. (2015, October 25). 10 Tips for Lead Poisoning Prevention Week 2015. Retrieved from https://calpoison.org/news/10-tips-lead-poisoning-prevention-week-2015

- Case Western Reserve University. (2010, June 15). Leaded gasoline predominant source of lead exposure in latter 20th century. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/06/100615141757.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013, October 15). Candy. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/tips/candy.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, February 18). Lead: Water. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/tips/water.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, February 4). Lead. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding: Lead. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/breastfeeding-special-circumstances/environmental-exposures/lead.html

- Centers for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas. (n.d.). Protect Your Family From Lead Poisoning. Retrieved from https://cerch.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/lead_safety.pdf

- Consumer Product Safety Commission. (n.d.). Recall List. Retrieved from https://www.cpsc.gov/Recalls

- Environmental Defense Fund. (2016, March 16). Lead remains a National Problem that Threatens the Health of All Americans Common-Sense Federal Actions Can Have Enormous Impact. Retrieved from http://blogs.edf.org/health/files/2016/03/Lead-poisoning-prevention-EDF-Plan-3-16-16.pdf

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2017, June). Protect Your Family from Lead in the Home. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-06/documents/pyf_color_landscape_format_2017_508.pdf

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2019 December). Federal Action Plan to Reduce Childhood Lead Exposure. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2018-12/documents/fedactionplan_lead_final.pdf

- Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). History of Reducing Air Pollution from Transportation in the United States. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/transportation-air-pollution-and-climate-change/accomplishments-and-success-air-pollution-transportation

- Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Learn about Lead. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/lead/learn-about-lead

- Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Protect Your Family from Exposures to Lead. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/lead/protect-your-family-exposures-lead

- Florida Department of Health. (n.d.). Information for Parents and Caregivers. Retrieved from http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/lead-poisoning/parent-info.html

- Jusko, T.A. et al. (2008, February). Blood Lead Concentrations < 10 μg/dL and Child Intelligence at 6 Years of Age. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2235210/

- Lewis, J. (1985, May). Lead Poisoning: A Historical Perspective. Retrieved from https://archive.epa.gov/epa/aboutepa/lead-poisoning-historical-perspective.html

- Mayo Clinic. (2016, December 6). Lead poisoning. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/lead-poisoning/symptoms-causes/syc-20354717

- National Capital Poison Center. (n.d.). Lead and Pregnancy: Know the Risks. Retrieved from https://www.poison.org/articles/lead-and-pregnancy

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. (2018, October 12). Lead. Retrieved from https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/lead/index.cfm

- Pederson, T. (2016, October 6). Facts About Lead. Retrieved from https://www.livescience.com/39304-facts-about-lead.html

- Stanford Children’s Health. (n.d.). Lead Poisoning in Children. Retrieved from https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=lead-poisoning-in-children-90-P02832

- Thayer, B. (2018, March 22). How to Fight Lead Exposure with Nutrition. Retrieved from https://www.eatright.org/health/wellness/preventing-illness/how-to-fight-lead-exposure-with-nutrition

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2012, August). Committee Opinion: Lead Screening During Pregnancy and Lactation. Retrieved from https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/Lead-Screening-During-Pregnancy-and-Lactation?IsMobileSet=false

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (n.d.). About Lead-Based Paint. Retrieved from https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/healthy_homes/healthyhomes/lead

- Warniment, C., Tasang, K., Galazka, S.S. (2010, March 15). Lead Poisoning in Children. Retrieved from https://www.aafp.org/afp/2010/0315/p751.html

- World Health Organization. (2018, August 23). Lead Poisoning and health. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lead-poisoning-and-health

- World Health Organization. Module Bi: Health Hazards of Lead. Retrieved from http://web.unep.org/sites/all/themes/noleadpaint/docs/Module%20Bi%20Health%20Impacts%20FINAL.pdf

Calling this number connects you with a Consumer Notice, LLC representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Consumer Notice, LLC's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.

844-420-1914