Indoor Air Quality

Indoor air pollutants can cause health problems ranging from allergies to asthma, and many pollutants are hard to detect. Fortunately, you can take several steps to eliminate sources of indoor air pollution or reduce their effects.

When you think about air pollution, you probably think about the air you breathe when you’re outside. But because we spend 90 percent of our time indoors — and indoor contaminants are usually more highly concentrated — it’s actually indoor air quality that more often affects us.

In fact, a growing body of research indicates that the air inside homes and office buildings is often dirtier than the air in some of the largest and most industrialized cities in the world, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. In other words, indoor air quality is an important environmental health issue.

Indoor air pollution can cause an array of unpleasant symptoms, including headaches, coughs, dizziness, fatigue, and irritation of the eyes, nose and throat. Usually these symptoms will resolve when the source of pollution is eliminated. In some cases, though, repeated exposure to air pollution can lead to long-term health problems, such as lung disease, heart disease and cancer.

Common Pollutants

Indoor air pollution has a variety of causes, including outdoor sources. Outdoor air pollution generated by burning fossil fuels, for instance, can flow inside buildings through cracks, gaps and ventilation systems and become indoor pollution.

Most of this pollution is particulate matter, or tiny particles of matter and droplets of liquid that can become suspended in the air and easily inhaled. Appliances that burn fuels for heating and cooking can also generate indoor particulate matter, as can tobacco smoke.

Other common indoor air pollutants include:

- Carbon Monoxide

- Radon

- Nitrogen dioxide

- Building material and furnishings

- Asbestos

- Building and paint products

- Household cleaning products

- Formaldehyde from pressed wood products and other sources

- Lead

- Mold and mildew

- Bacteria and viruses

- Pesticides

- Pet dander

- Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)

- Cockroach droppings, saliva and body parts

- Dust and dust mites

- Pollen

A lack of adequate ventilation can contribute to the buildup of contaminants and make indoor air pollution worse. Inadequate ventilation is the primary cause of half the workplace indoor air investigations conducted by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Mold

Elevated humidity and high temperatures can also worsen indoor pollution by creating an environment that’s ripe for the growth of biological pollutants, such as mold and bacteria.

Molds are types of fungi that need moisture to grow. In nature, mold is useful because it helps to break down dead and decaying matter. But indoors, it can wreak havoc. Mold spores can become airborne and irritate your skin, eyes, nose, throat and lungs. Mold can also trigger allergy attacks and asthma episodes.

You can prevent and slow mold growth by keeping humidity levels at 50 percent or less, and keeping showers and cooking areas well ventilated. If you end up with a mold problem, you need to correct the issue that’s causing it and clean it up completely.

You can also prevent a mold infestation by:

- Identifying hidden leaks

- Fixing leaks and water damage quickly

- Performing routine maintenance and repairs

- Using a dehumidifier

- Using your stove’s exhaust hood to draw heat and moisture outside

- Making sure clothes dryers are vented to the outdoors

- Installing drain gutters to keep water away from your house’s foundation

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, you can remove mold from hard surfaces with soap and water or with a homemade bleach solution made from no more than 1 cup of household laundry bleach and 1 gallon of water. If mold contamination is more severe, you may need to hire a professional.

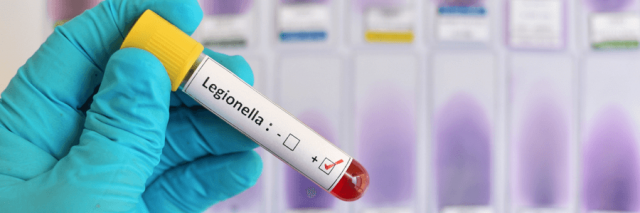

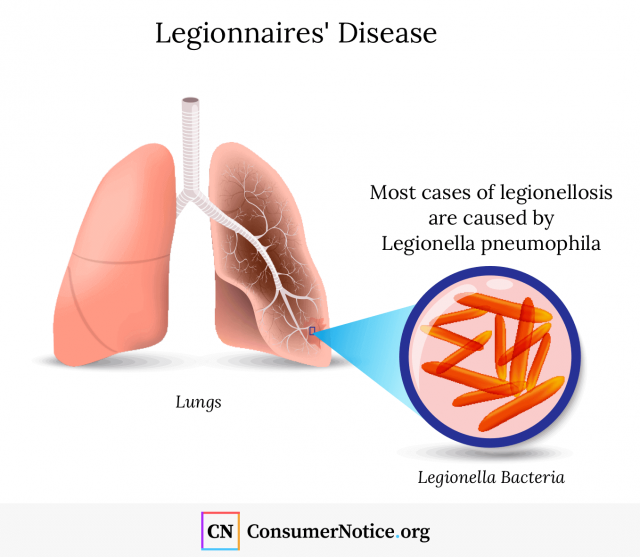

Legionella

Large water systems, such as those found in hospitals, hotels and cruise ships, can also harbor dangerous bacteria that may cause serious health problems.

Legionella, the bacterium that causes Legionnaires’ disease, occurs naturally in lakes and streams. But when it infiltrates building water systems, it can multiply out of control. People become sick when they unknowingly inhale tiny aerosolized droplets of the tainted water.

Cooling towers associated with large-scale air conditioning systems are one of the leading causes of Legionnaires’ outbreaks. As part of a study published in 2017 in PLOS One, researchers tested 196 cooling towers in eight of the nine continental United States climate regions. Overall, 84 percent were contaminated with Legionella bacteria.

Other common reservoirs for legionella include:

- Hot and cold water storage tanks

- Water filters

- Ice machines

- Hot tubs

- Evaporative air conditioners

- Decorative fountains

- Faucets

- Showerheads and hoses

- Faucet flow restrictors

- Pipes, valves and fittings

- Centrally installed misters and humidifiers

- Certain types of medical equipment, such as CPAP machines, bronchoscopes and nebulizers

Symptoms of Legionnaires’ disease include coughing, headaches, muscle aches, fever and trouble breathing. With antibiotics, most people will completely recover from the illness, but 1 in 10 people who develop Legionnaires’ pneumonia will die.

You can minimize the risk of Legionella at home by properly maintaining plumbing systems. It’s important to regularly flush your pipes with warm or hot water and not let water stagnate. You should also regularly clean showerheads.

If you have a fountain or a hot tub, you need to regularly drain and disinfect it. Humidifiers should also be emptied, cleaned and rinsed each day. If you use a nebulizer, rinse the bowl each time you use it and wash the entire chamber and mask every day with warm water and dishwashing liquid. Only use distilled water or water that’s been boiled in your nebulizer.

Radon Gas

Radon is the second leading cause of lung cancer after smoking. Radon is a radioactive gas that develops from the breakdown of uranium and other radioactive metals in soil, rocks and groundwater.

Because it occurs naturally, everyone is exposed to low levels of radon. This normal level of exposure is not usually considered dangerous. But if radon seeps into your home through cracks and crevices, high levels of the gas can accumulate and threaten your health.

Because radon has no smell or taste, and you can’t see it, it’s impossible to know it’s there unless you test for it.

Most home improvement stores sell inexpensive radon test kits. You can also purchase a radon test kit online from Kansas State University’s National Radon Program Services. Short-term test kits cost $15 and take two to four days. Long-term radon test kits take three to 12 months and cost $25. New Jersey residents must pay $10 extra because of state requirements.

The average level of radon indoors is approximately 1.3 picocuries per liter (pCi/L), according to the EPA. If your test shows radon levels of 4 pCi/L or higher, you’ll need to do a confirmation test and take steps to reduce radon levels.

Sealing cracks and increasing ventilation can help reduce radon levels, but the EPA recommends you hire a qualified contractor with experience in radon reduction techniques.

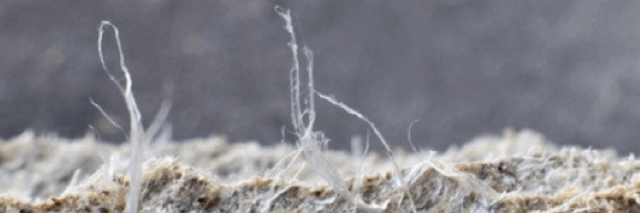

Asbestos

Asbestos is a naturally occurring fibrous mineral that’s strong, flexible and heat resistant. Those qualities have made it a popular component in a variety of building materials, including insulation, vinyl flooring, roofing shingles, textured paint and other products.

But when inhaled or ingested, asbestos fibers are toxic to humans. Asbestos is the leading cause of mesothelioma, an aggressive and lethal cancer that affects the lining of the lungs, abdomen, heart and other organs.

While some uses of asbestos are currently banned, many are not. And older homes, in particular, may have hidden asbestos everywhere.

Asbestos becomes dangerous when it’s damaged or disturbed and tiny asbestos fibers go airborne. That’s why it’s critical to take precautions if you’re planning a home remodeling project. An asbestos professional can help you identify whether your home contains asbestos and take steps to reduce any potential exposure.

Asthma Triggers

Air pollution is a common trigger for asthma, a chronic lung disease that inflames and constricts the airways. Typical symptoms of asthma include shortness of breath, coughing and wheezing. Severe asthma attacks can be life-threatening.

Many common triggers, however, are invisible to the naked eye.

Dust mites, for instance, are microscopic, insect-like pests that feed off of the dead skin of people and pets. Even though you can’t see them, they are ever present and live in bedding, furniture, carpet, drapes and other places.

Other common indoor pollutants that can trigger asthma include:

- Pollen

- Molds

- Tobacco smoke and vape products

- Pet dander

- Cockroach droppings

To reduce tobacco exposure, don’t allow smoking inside your house. Require those who do smoke to wear a specific jacket over their clothes when they smoke outside so they don’t bring “thirdhand” smoke, or tobacco residue, indoors with them.

To cut down on pests like cockroaches, keep garbage outside of the home and don’t leave dirty dishes stacked in the sink. Standing water also attracts roaches, so fix any potential plumbing leaks and seal any crevices or cracks around pipes.

Be sure to vacuum frequently to help eliminate pollen, pet dander and dust. Also, wash your bedding frequently and consider investing in allergy-proof pillows and mattress covers.

Secondhand Smoke

Secondhand smoke contains more than 7,000 substances and remains a major contributor to indoor air pollution, according to the EPA.

Exposure to secondhand smoke has been linked to heart disease, stroke, lung cancer, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and other ailments, and nonsmokers who breathe in secondhand smoke have a 20 percent to 30 percent higher risk of lung cancer.

Some people falsely believe that opening a window or using a filtration system will get rid of smoke. Ventilation and filtration may reduce secondhand smoke, but they can’t eliminate it. Secondhand smoke also travels from room to room within a house and can even spread between apartments.

As such, the only way to eliminate secondhand smoke and the risks associated with it is to prohibit smoking indoors.

Carbon Monoxide

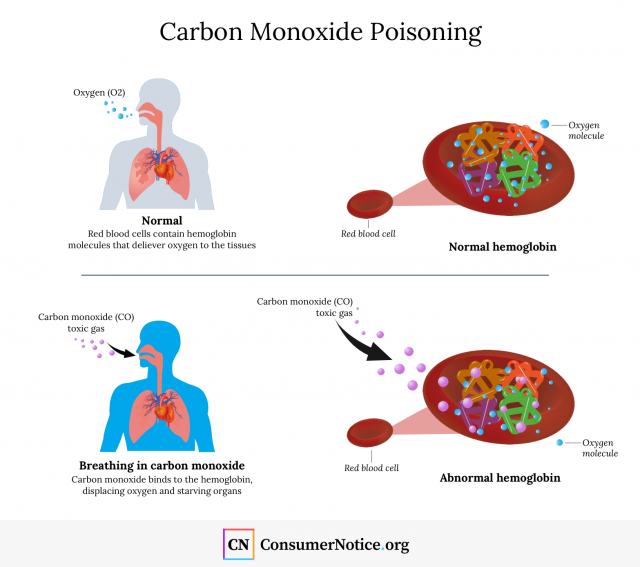

Carbon monoxide, or CO, is an invisible and deadly killer. The toxic gas has no distinctive odor or taste, but it has a pronounced effect on your body.

When you inhale CO, it enters your blood stream and attaches to hemoglobin. Normally hemoglobin transports oxygen to all your cells, but CO crowds out oxygen, and your oxygen-deprived cells begin to die.

At low levels, CO exposure can cause fatigue. Individuals with heart issues might also experience chest pain. At high levels, carbon monoxide triggers headaches, dizziness, confusion, nausea and other flu-like symptoms. It can also kill you.

Common sources of carbon monoxide include:

- Leaking chimneys or furnaces

- Generators and other gas-powered equipment

- Backdrafts from furnaces, gas water heaters, wood stoves, fireplaces and gas stoves

- Gas space heaters and unvented kerosene heaters

- Automobile exhaust generated by an idling car in attached garage

- Faulty gas ranges

- Blocked, disconnected or improperly sized fireplace flues

Because of these dangers, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission urges you to install a carbon monoxide detector on each level of your home. The watchdog agency also recommends you have all fuel-burning appliances inspected annually to check for potential CO leaks.

Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)

Volatile organic compounds, also known as VOCs, include a number of different chemicals found in thousands of common household products, such as paints, varnishes, waxes, cosmetics, cleansers and disinfectants.

The term volatile means they vaporize, or turn into a gas, very easily at room temperature.

These organic compounds are released into the air when you use the product, but they’re also emitted while they’re being stored. While VOCs are found everywhere, the concentrations of these chemicals are two to five times higher indoors, on average, than outdoors, according to the EPA.

Common sources of VOCs include:

- Aerosol sprays

- Household cleaning products

- Paints and paint strippers

- Hobby and craft supplies

- Moth repellents

- Air fresheners

- Pesticides

- Clothes that have been dry-cleaned

- Automotive products

- Copy machines and printers

- Glues and adhesives

- Permanent markers

Exposure to VOCs can cause a wide range of health effects. Short-term exposure to VOCs can cause irritation of your mucous membranes, headaches, visual disturbances and memory problems.

Longer exposure will also bother your eyes, nose and throat. In addition, you may also experience nausea, fatigue, dizziness and a loss of coordination. Long-term VOC exposure can also damage your liver, kidneys and central nervous system, and cause cancer.

Young children, people with asthma and the elderly may have more severe reactions to VOC exposure.

Avoiding Formaldehyde and Other VOCs

One of the most well known VOCs is formaldehyde. Common items that emit formaldehyde include pressed wood products, wood floor finishes and wallpaper.

Some types of fabric, drapes and foam insulation contain formaldehyde, too. Cigarette smoke also produces formaldehyde, as does burning wood, oil, gasoline and other combustible materials.

And porous products, such as carpet and gypsum board, can absorb formaldehyde that’s been emitted by other products and release it later, according to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission.

The commission offers the following tips to reduce your exposure to VOCs:

- Avoid secondhand smoke and if you smoke, quit.

- Ventilate well when using products that contain VOCs and air out your house when you bring home new furnishings.

- Store unused chemicals in your garage or shed.

- Remove dry cleaned clothing from plastic bags and air them out near a window or outside.

Try to reduce that number of products you own that release VOCs. Opt for low-VOC paints and furnishings and choose solid wood items rather than composite wood.

And avoid buying clothes made from fabric with durable-press finishings, such as rayon, corduroy and wrinkle-resistant cotton. These fabrics are more likely to contain formaldehyde. If you do buy them, wash them before you wear them.

36 Cited Research Articles

Consumernotice.org adheres to the highest ethical standards for content production and references only credible sources of information, including government reports, interviews with experts, highly regarded nonprofit organizations, peer-reviewed journals, court records and academic organizations. You can learn more about our dedication to relevance, accuracy and transparency by reading our editorial policy.

- Allen, J.G. et al. (2015). Green Buildings and Health. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4513229/

- American Cancer Society. (2018, November 19). How to Test Your Home for Radon. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/latest-news/radon-gas-and-lung-cancer.html

- American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. (2015). Indoor Air Pollutants. Retrieved from https://smarterhouse.org/ventilation-and-air-distribution/indoor-air-pollutants

- American Lung Association. (2018, June 19). Indoor Air Pollutants and Health. Retrieved from https://www.lung.org/clean-air/at-home/indoor-air-pollutants

- Bourbeau, J., Brisson, C. & Allaire, S. (1996, March). Prevalence of the sick building symptoms in office workers before and after being exposed to a building with an improved ventilation system. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1128445/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, January 17). Secondhand Smoke (SHS) Facts. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/secondhand_smoke/general_facts/index.htm

- City of Marshfield Wisconsin. (n.d.). Asbestos in Older Homes. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20201028112515/http://ci.marshfield.wi.us/Asbestos_in_older_homes.pdf

- Government of Canada. (2017, September 11). Volatile organic compounds. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/air-quality/indoor-air-contaminants/volatile-organic-compounds.html

- Government of Western Australia. (n.d.) Minimising the risk of a Legionella infection at home. Retrieved from https://www.healthywa.wa.gov.au/Articles/J_M/Minimising-the-risk-of-a-Legionella-infection-at-home

- Illinois Department of Public Health. (n.d.). Environmental Health Fact Sheet: Air Quality in the Home. Retrieved from http://www.idph.state.il.us/envhealth/factsheets/airquality.htm

- Joshi, S.M. (2008, August). The sick building syndrome. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2796751/

- Kansas State University National Radon Program Services. (n.d.). Radon Test Kits Available for Purchase. Retrieved from https://sosradon.org/test-kits

- Lara, A.R. (2018, March). Building-Related Illnesses. Retrieved from https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/lung-and-airway-disorders/environmental-lung-diseases/building-related-illnesses

- Llewellyn, A.C. et al. (2017, December 20). Distribution of Legionella and bacterial community composition among regionally diverse US cooling towers. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0189937

- Marmot, A.F. et al. (2006, April). Building health: an epidemiological study of “sick building syndrome” in the Whitehall II study. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2078095/

- Mueller, D. et al. (2011). Tobacco smoke particles and indoor air quality (ToPIQ) — the protocol of a new study. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3260229/

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016, September 26). Health Risks of Indoor Exposure to Particulate Matter. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK390376/

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. (2019, December 28). Dust Mites and Cockroaches. Retrieved from https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/allergens/dustmites/index.cfm

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. (2019, February 19). Air Pollution. Retrieved from https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/air-pollution/index.cfm

- Safety and Health Magazine. (2012, April 1). Linking illness to indoor air quality. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandhealthmagazine.com/articles/print/linking-illness-to-indoor-air-quality-2

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (1999). Health Effects of Exposure to Radon. Retrieved from https://www.nap.edu/read/5499/chapter/1#ii

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (2015). An Update on Formaldehyde. Retrieved from https://www.cpsc.gov/PageFiles/121919/AN_UPDATE_ON_FORMALDEHYDE-update03102015.pdf

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2003, June). EPA Assessment of Risks from Radon in Homes. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-05/documents/402-r-03-003.pdf

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2014, August). Typical Indoor Air Pollutants. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-08/documents/refguide_appendix_e.pdf

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Asbestos. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/asbestos

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Carbon Monoxide’s Impact on Indoor Air Quality. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/carbon-monoxides-impact-indoor-air-quality

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Care for Your Air: A Guide to Indoor Air Quality. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/care-your-air-guide-indoor-air-quality

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Health Risk of Radon. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/radon/health-risk-radon

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Indoor Air Pollution: An Introduction for Health Professionals. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/indoor-air-pollution-introduction-health-professionals#humidifier

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Indoor Air Quality (IAQ). Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Protect Indoor Air Quality in Your Home. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/protect-indoor-air-quality-your-home

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Radon. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/radon

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). The Inside Story: A Guide to Indoor Air Quality. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/inside-story-guide-indoor-air-quality

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Wood Smoke and Your Health. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/burnwise/wood-smoke-and-your-health

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2017, May 31). Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs). Retrieved from https://toxtown.nlm.nih.gov/chemicals-and-contaminants/volatile-organic-compounds-vocs

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2018, December 28). Indoor Air Pollution. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/indoorairpollution.html

Calling this number connects you with a Consumer Notice, LLC representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Consumer Notice, LLC's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.

844-420-1914