Coal Tar Sealants

Coal tar sealant is a thick, black goop applied to driveways, asphalt parking lots and playgrounds, primarily in the eastern United States. The sealcoat contains high levels of toxic chemicals that can cause cancer and environmental harm.

Manufacturers encourage consumers to use coal tar sealant every few years to brighten up and protect their asphalt pavement surfaces. And sealcoating, as it’s sometimes called, is widespread. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that 85 million gallons of coal tar-based sealant — enough to cover 170 square miles — is laid down each year.

But the shiny, black sealant contains toxic compounds known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs, which can seep into the environment. As a result, several cities have banned the sale and use of the product, and some localities are suing coal tar sealant manufacturers to get them to pay for the costly environmental cleanups.

PAH Contaminants

PAHs give newly paved parking lots their characteristic smell, but the compounds are dangerous. PAHs are poisonous to fish and other aquatic life, and they’ve been linked to cancer in humans.

PAHs develop whenever carbon is heated or combusted. As such, the contaminants are common in used motor oil, industrial emissions and automobile tires. They’re also plentiful in coal tar pitch, which is a key ingredient in coal tar paver.

More than 200 types of PAH compounds are found in coal tar pitch, and at least seven types of PAHs are classified by the Environmental Protection Agency as probable human carcinogens.

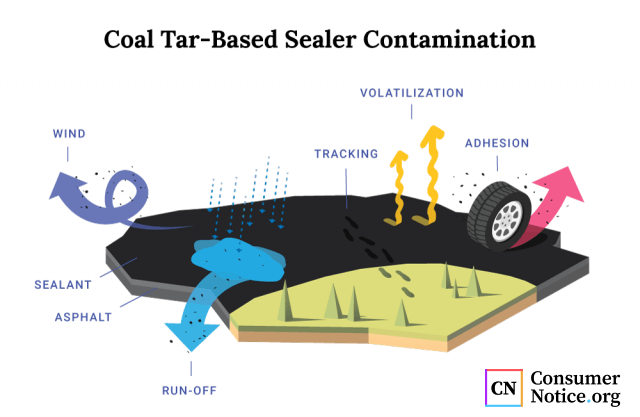

The key problem with coal tar-based sealcoat is that it doesn’t stay put. After it dries, it flakes off as a dust and spreads everywhere.

At the 2017 Emerging Contaminants in the Aquatic Environment Conference, Barbara Mahler, a research hydrologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, explained how sealcoat dust washes into stormwater, is blown around by the wind and sticks to tires. It also sticks to people’s shoes and they can track the PAH-laden dust into their homes and offices.

PAHs can also vaporize — or volatilize — into the air. And homes in close vicinity to treated pavement have been found to have dust with PAH concentrations 25 times higher than normal.

Mahler said the first clue that coal tar pavement sealers were causing serious environmental health problems surfaced in the early 2000s when the City of Austin detected high levels of PAHs in local streams. The contaminants there measured at 1,000 parts per million. To put it in perspective, that’s about 43 times the amount one would expect to find at a federally designated Superfund hazardous waste site, according to Mahler.

When a member of the research team looked upstream to find the source of the contamination, the team member realized it was coming from the pavement sealcoat. After the city’s discovery, the U.S. Geological Survey began researching the problem. The agency found that most of PAH contamination in Austin streams was indeed coming from coal tar sealants.

But it wasn’t just an Austin problem. PAH contamination was running rampant all over the United States, east of the Mississippi. In 2010, U.S. Geological Survey scientists discovered sealant contamination in 40 urban lakes they studied.

What Are the Health Risks?

As coal tar sealant dust spreads, humans and animals can inhale it, swallow it or absorb it through their skin, and the toxic chemicals can wreak havoc on living organisms.

Children who live near parking lots coated with tar-based sealcoats ingest 14 times more PAHs than those who live next to unsealed lots, according to a 2012 study published in the Environmental Pollution journal.

The same study, which was conducted by researchers at Baylor University and the U.S. Geological Survey, found that people living next to pavement coated with coal tar-based sealants have a cancer risk 38 times higher on average than those who don’t live in close proximity to the pavement sealer.

Cancers Linked to PAH Exposure

- Lung cancer

- Skin cancer

- Bladder cancer

- Gastrointestinal cancers

The PAHs released by the pavement coating can also cause cancer, birth defects and deaths in fish, insects and other organisms, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Manufacturers of coal tar-based sealcoat will sometimes say that the product is safe and won’t contaminate other areas if it’s given 24 to 48 hours to cure and no one drives on it or uses it during that time. But according to the U.S. Geological Survey, the toxic effects can occur long after that period and are especially severe when organisms are exposed to sunlight.

In a U.S. Geological Survey experiment, researchers exposed minnows and water fleas to coal tar sealant runoff. Up to 42 days later, the runoff caused all the animals to die. When the minnows and water fleas were also exposed to UV light, the 100 percent mortality rate continued for up to 111 days after the sealcoat application.

Sealcoat Bans and Alternatives

As awareness of the dangers of coal tar-based sealcoating has spread, state and local governments have begun banning the use of the products.

In 2006, Austin became the first United States city to ban the use of coal tar-based pavement sealants, and the crackdown appears to be working. By 2014, the level of PAH contaminants in Lady Bird Lake, a river-like reservoir on Austin’s Colorado River, declined by 58 percent, according to a U.S. Geological Survey study.

Several other cities and counties have followed suit, enacting bans and instituting enforcement actions for those who violate the bans. In Austin, for instance, the courts can require a person who violates the ban to clean up any contamination caused by application of the sealant. Violators can also face fines and jail time.

Some of the cities, counties and states that have banned the use of coal tar-based sealants include:

- Austin, Texas

- Dane County, Wisconsin

- District of Columbia

- Minnesota

- Montgomery County, Maryland

- Prince George’s County, Maryland

- Suffolk County, New York

- Washington state

But cleaning up lakes and ponds already polluted with PAHs is an expensive endeavor. It can cost hundreds of millions of dollars, according to some estimates. As a result, some cities are suing the products’ manufacturers to try to get them to pay for the damage.

Eight Minnesota cities, for instance, have filed coal tar pavement sealant lawsuits to try to cover their cleanup costs. According to the White Bear Press, the cleanup costs include monitoring and testing of stormwater sediments as well as disposing of the tainted muck.

Alternatives and Removal

As cities continue to cope with PAH water contamination, consumers can do their part by choosing the right products and avoiding coal-tar based sealants.

Asphalt-based sealants are much more environmentally friendly than coal tar-based sealants. The levels of PAH in asphalt products are up to 1,000 times lower. Other alternatives with minimal levels of PAH include acrylic sealants and gravel parking lots.

If you’re sealcoating your own driveway, only choose products that have the “coal tar free” label. If you’re hiring a contractor, ask them for the MSDS, or material data safety sheet, for the product they intend to use. You want to avoid any product with the code for “coal tar” or “pitch,” which is 65996-93-2.

The group Coal Tar Free America also suggests that people use the following cheap and easy field test to see if pavement contains coal tar.

- Step 1

- Using a screwdriver or knife, scrape a tiny amount of material off your pavement and place it in a small glass container.

- Step 2

- Add a small amount of paint thinner (mineral spirits) to the container and close it tightly.

- Step 3

- Gently swirl the solution and then allow it to sit for a few minutes.

- Step 4

- Analyze the color of the solution. If it looks like coffee, then it’s most likely an asphalt-based sealant, which is safe. If it resembles tea, then you’re dealing with coal tar-based sealant. If the solution is a reddish hue, then it’s most likely a blend of the two.

If you discover that your driveway is covered with coal tar sealant, you can hire contractors to remove it. They’ll use a specialized process known as shot-blasting, which literally blasts small steel beads to remove the top layer of sealant. They’ll then dispose of the waste in heavy-duty trash bags or by placing it in a removable dumpster.

Another option is to cover the existing layer with an asphalt-based product to prevent it from escaping.

28 Cited Research Articles

Consumernotice.org adheres to the highest ethical standards for content production and references only credible sources of information, including government reports, interviews with experts, highly regarded nonprofit organizations, peer-reviewed journals, court records and academic organizations. You can learn more about our dedication to relevance, accuracy and transparency by reading our editorial policy.

- Baldwin, A.K. et al. (2016, November 24). Primary sources and toxicity of PAHs in Milwaukee-area streambed sediment. Retrieved from https://setac.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/etc.3694

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (1995, August). Retrieved from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/phs/phs.asp?id=120&tid=25

- City of Austin. (n.d.). Watershed Protection Department: Coal Tar. Retrieved from http://www.austintexas.gov/department/coal-tar

- City of Austin. (n.d.). Watershed Protection Department: Coal Tar Remediation. Retrieved from https://austintexas.gov/faq/pah-remediation

- Clean Wisconsin. (n.d.). Dangerous Driveways Toxic PAH Pollution From Tar-Based Sealants. Retrieved from https://www.elmgrovewi.org/AgendaCenter/ViewFile/Item/5195?fileID=4634

- Coal Tar Free America. (n.d.). Field Test for Coal Tar Sealant Determination. Retrieved from https://coaltarfreeusa.com/2010/12/field-test-for-coal-tar-sealant-determination/

- District Department of Energy & Environment. (2011, October 20). District Orders Removal of Toxic Coal Tar Sealant From Private Parking Lot. Retrieved from https://doee.dc.gov/release/district-orders-removal-toxic-coal-tar-sealant-private-parking-lot

- District Department of Energy & Environment. (n.d.). Coal Tar Ban in the District of Columbia. Retrieved from https://doee.dc.gov/coaltar

- Environmental and Energy Study Institute. (2016, August 17). Retrieved from https://www.eesi.org/articles/view/health-concerns-over-common-driveway-sealant-continue-to-prompt-local-bans

- Hawthorne, M. (2011, January 18). New doubts cast on the safety of common driveway sealant. Retrieved from https://www.chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/health/ct-met-toxic-coal-tar-sealant-20110115-story.html

- Illinois Department of Public Health. (n.d.). Cancer in Illinois: Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs). Retrieved from http://www.idph.state.il.us/cancer/factsheets/polycyclicaromatichydrocarbons.htm

- Illinois Sustainable Technology Center. (2017, June 8). PAHs and coal tar — old contaminants with emerging concerns. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=53qRye3dJk0

- Koch, W. (2013, June 16). Toxic driveways? Cities ban coal tar sealants. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/business/2013/06/16/toxic-driveways-cities-states-ban-coal-tar-pavement-sealants/2028661/

- Mahler, B. (2012, March 20). Coal-Tar-Based Pavement Sealcoat and PAHs: Implications for the Environment, Human Health, and Stormwater Management. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3308201/

- Needleman, H. (2015). The Use, Impact, and Ban of Coal Tar-Based Sealants. Retrieved from https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/vcpclinic/28/

- Needleman, H. (2015). The Use, Impact, and Ban of Coal Tar-Based Sealants. Retrieved from https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/vcpclinic/28/

- Oregon State University. (2016, April 27). Coal-tar based sealcoats on driveways, parking lots far more toxic than suspected. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/04/160427151028.htm

- Schulte, P.A. (2006, April). Coal Tar and Paving Products. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1440806/

- The Village of Deerfield. (n.d.). Coal Tar Sealant Ban. Retrieved from https://www.deerfield.il.us/708/Coal-Tar-Sealant-Ban

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2012, November). Coal-Tar Sealcoat, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, and Stormwater Pollution. Retrieved from https://www3.epa.gov/npdes/pubs/coaltar.pdf

- U.S. Geological Survey. (2010, December 1). Coal Tar Sealant Largest Source of PAHs in Lakes. Retrieved from https://archive.usgs.gov/archive/sites/www.usgs.gov/newsroom/article.asp-ID=2651.html

- U.S. Geological Survey. (2014, June 16). Austin Coal-Tar Sealant Ban Leads to Decline in PAHs. Retrieved from https://www.usgs.gov/news/austin-coal-tar-sealant-ban-leads-decline-pahs

- U.S. Geological Survey. (2017, January 19). You’re standing on it! Coal-tar-based pavement sealcoat, PAHs, and Environmental Contamination. Retrieved from https://19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-12/documents/coal-tar-based-pavement-sealcoat-pahs-and-environmental-contamination.pdf

- U.S. Geological Survey. (n.d.). Coal-Tar-Based Pavement Sealcoat, PAHs, and Environmental Health. Retrieved from https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/coal-tar-based-pavement-sealcoat-pahs-and-environmental-health?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects

- University of New Hampshire. (n.d.). Thinking of Sealcoating Your Driveway? Get the Facts! Retrieved from https://www.unh.edu/unhsc/sites/unh.edu.unhsc/files/UNHSC%20Seagrant%20sealcoat%20fact%20sheet.pdf

- Van Metre, P.C. et al. (2006, January). Parking Lot Sealcoat: A Major Source of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Urban and Suburban Environments. Retrieved from http://www.ci.austin.tx.us/watershed/downloads/USGSfactSheet12_29_v2.pdf

- Verges, J. (2019, January 3). Retrieved from https://www.twincities.com/2019/01/02/minnesota-cities-sue-makers-of-banned-driveway-sealant-alleging-1-billion-pond-problem/

- Williams, E. S., Mahler, B.J. & Van Metre, P.C. (2012, May). Coal-tar pavement sealants might substantially increase children’s PAH exposures. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749112000279

Calling this number connects you with a Consumer Notice, LLC representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Consumer Notice, LLC's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.

844-420-1914