Water Contamination

Water contamination occurs when substances pollute the water and make it unusable for cooking, drinking and other uses. Contamination can occur from agriculture, industrial chemicals, overflowing sewers and more. Knowing the signs of water contamination will help keep you and your family safe.

How Water Contamination is Caused

Water contamination is caused by harmful substances, such as chemicals or microorganisms, entering a water source. Agricultural runoff, industrial contamination, improperly treated water, natural disasters and sewage leaks are some of the main causes.

Agricultural Runoff

Agricultural runoff is one of the biggest sources of water pollution, and industrial agricultural operations are some of the worst offenders. Crop production and livestock each generate significant amounts of waste and runoff that can seep into water supplies.

- Animal fecal waste containing bacteria, viruses and other pathogens.

- Antibiotics, hormones, salts and heavy metals excreted by livestock.

- Fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides.

Water supplies can also be contaminated through the drinking water disinfection process. Water additives, such as chlorine and chloramines, are used to control the growth of microbes. But when levels are too high, they can cause eye and nose irritation, stomach upset and other problems.

Camp Lejeune Water Contamination

Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune water contamination occurred from 1953 to 1987 when toxic chemicals such as trichlorethylene (TCE), perchloroethylene (PCE), benzene and vinyl chloride polluted water treatment plants that supplied the base.

The chemicals came from a nearby dry-cleaning facility that was improperly dumping chemicals. On-base leaks and spills also contributed to contamination.

People exposed to contaminated water began filing Camp Lejeune lawsuits after they developed cancer and other health problems.

Flint, Michigan

Water that’s not properly treated or that travels through poorly maintained pipes can also pose a health hazard. If your water is acidic, corrosion of copper and lead pipes can occur and contaminate it.

That’s what happened in Flint, Michigan, in 2014 when city officials decided to start using the Flint River as an alternative water source until a new water pipeline from Lake Huron was built. The new water was cheaper than the water Flint had previously been pumping in from Detroit. But it wasn’t treated with an important anti-corrosive agent to deter lead contamination.

Soon, the city’s water turned brown and consumers began complaining that it was causing skin rashes, hair loss and other problems. Because officials failed to treat the corrosive river water, it was leaching lead out of the city’s aging pipes and sending it through thousands of taps. Studies later revealed that local children’s blood-lead levels had doubled or even tripled in some cases.

Water Disinfection, Weather and Other Causes

Water disinfection can also cause the formation of dangerous byproducts, such as bromates, haloacetic acids and trihalomethanes — all of which can increase your risk of cancer. Other byproducts, such as chlorite, can cause anemia and nervous system problems in babies and children.

- Industrial activities, such as mining and foundries.

- Runoff from soil, air pollution and automobile emissions.

- Malfunctioning wastewater treatment systems, such as septic tanks.

- Leaking underground storage systems and pipes.

- Landfill leakage.

- Sewer overflows.

- Radiation leaks from nuclear power plants.

Even weather can adversely affect water quality. High temperatures and warmer waters can cause harmful algae blooms. Toxic blue-green algae prefer warm, slow-moving water. They’re also triggered by excessive levels of nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus.

Types of Water Contamination

Numerous types of contaminants can threaten drinking water. They include chemicals and pesticides, animal waste and industrial waste injected into the ground. Naturally occurring substances such as arsenic, radon and fluoride can also contaminate groundwater.

Toxic chemicals such as those found in the water supply at Camp Lejeune include trichlorethylene (TCE), perchloroethylene (PCE), benzene and vinyl chloride. The risk of exposure to these chemicals is higher if you live near military bases or industrial sites.

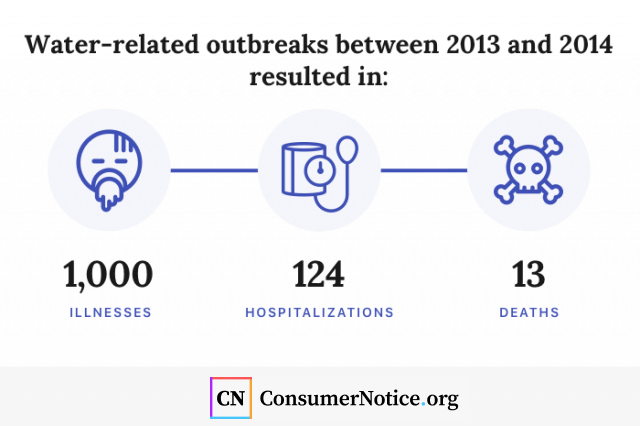

Waterborne pathogens, including bacteria, viruses and parasites, can also contaminate water. Between 2013 and 2014, more than three dozen water-related outbreaks were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These outbreaks resulted in more than 1,000 illnesses, 124 hospitalizations and 13 deaths.

- Giardia

- Legionella

- Norovirus

- Shigella

- Campylobacter

- Copper

- Salmonella

- Hepatitis A

- Cryptosporidium

- E. coli and excessive fluoride (tie)

These contaminants can lead to severe illness, including gastrointestinal upset, neurological problems and reproductive issues. They are especially dangerous to the very young and very old and to those with compromised immune systems.

In recent years, there have also been reports of pharmaceutical drugs in the water supply. Fortunately, the concentrations of these drugs are extremely low and unlikely to cause any considerable health effects, according to a 2012 study by the World Health Organization.

What Are PFAS Chemicals?

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, known as PFAS, are also of concern. The manmade chemicals have been used for decades in everything from nonstick pots and pans to stain protectants on carpets, clothing and upholstery. They are also used in firefighting foams.

The hazardous compounds are sometimes referred to as “forever chemicals” because they don’t break down in nature or in the body. They’ve also been linked to a wide variety of health problems, including several types of cancer, birth defects, endocrine and immune system problems, and elevated cholesterol.

While two common PFAS — perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) — have been phased out by United States industry, they are still used internationally and imported into the country.

A recent study by the Environmental Working Group and Northeastern University’s Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute pinpointed PFAS contamination at locations in 43 states, including drinking water sites serving approximately 19 million people.

Military sites were among those most affected by the problem. The chemicals likely contaminated the environment and groundwater on military bases when flame-resistant firefighting foam was used during training and emergency response exercises.

Communities near manufacturing sites have also discovered high levels of PFAS contamination of their water supplies.

In 2016, the village of Hoosick Falls, New York, discovered high levels of the cancer-causing compounds in its public drinking water supply and private drinking water wells. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, a person’s exposure level to PFAS, including PFOA and PFOS, in drinking water should not exceed 70 parts per trillion in a lifetime. In Hoosick Falls, some samples detected PFOA levels at 130,000 parts per trillion.

The state of New York has accused two local companies, Saint-Gobain Performance Plastics and Honeywell International, of causing the pollution. Saint-Gobain Performance Plastics was also implicated in a PFOA drinking water contamination near the company’s factory in Merrimack, New Hampshire.

Health Complications of Contaminated Water

Contaminated water can cause considerable health problems, ranging from gastrointestinal illnesses to neurological problems to cancer.

In the case of pathogens that cause waterborne disease, the effects are usually noticed rapidly. A person who drinks water containing bacteria or a virus will often develop diarrhea, nausea, vomiting and other acute gastrointestinal symptoms. In severe cases, these symptoms can lead to dehydration and death.

Likewise, ingesting large amounts of copper-contaminated water may cause nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Extremely high amounts can cause liver and kidney damage and even death.

But other types of contamination are more insidious. Signs and symptoms of lead exposure, for instance, typically won’t appear until dangerous levels have accumulated in a person’s body. The toxic metal can cause lifelong complications. Infants and children exposed to lead may have developmental delays, learning difficulties and behavioral problems. And the health impacts of PFAS and other contaminants can take years to show up.

Protecting Yourself From Water Contamination

If you suspect something is wrong with your tap water, contact your public water utility immediately. You may also wish to have your household water tested. The EPA provides a list of certified laboratories.

- It Looks Funny

- Your tap water should always be clear. If it looks cloudy or milky, set it down for a few minutes to see if it clears up. If it does, your water might have just contained trapped air bubbles. If it stays cloudy or foamy, your water could contain elevated levels of heavy minerals or something worse. In that case, it’s time to get your water tested.

- It Smells Strange

- If your water has an unusual smell, it could be contaminated, but often contaminants have no smell. A strong rotten egg smell can indicate that your water contains high levels of sulfur. This is usually not dangerous, but it can be unappetizing. Likewise, if your water tastes like a swimming pool, it may contain high levels of chlorine. A water filter may help eliminate excess chlorine and sulfur.

- It Tastes Funny

- Often contaminants have no taste, but in some cases they might. In Flint, Michigan, residents said the water tasted strange, smelled bad and had a brownish color.

According to a 2017 article in the journal Applied Water Science, most contaminants can’t be easily detected and testing is needed to identify them.

If you have reason to believe your water supply is contaminated, switch to using bottled water for cooking, drinking, brushing your teeth and making ice.

In some situations, boiling your water will make it safe to consume. If your water authority issues a boil water advisory, bring your water to a vigorous boil for one minute. This will ensure that all bacteria and other microbes are killed and will make the water safe.

Unfortunately, boiling water won’t get rid of other types of contaminants and may even make the water worse. Boiling water that contains PFAS, for instance, will actually concentrate the chemicals and increase your health risks.

There are also a number of things you can do to reduce the pollution of you household water.

- DO Catch Runoff. Use gravel, paver stones and other porous materials to stop the flow of stormwater around your home before it pours into storm drains.

- DO Pick Up After Your Dog. Pet waste is laden with bacteria and can easily contaminate storm drains and water supplies. Pick up poop in a recycled bag and put it in your garbage.

- DO Maintain Your Car. When your car leaks oil, coolant and other fluids, rainwater takes it right into the groundwater. Keep your car in good condition and also wash it in a commercial car wash. It’s better than discharging polluted water down your driveway.

- DO Shop with Pollution in Mind. Reducing your use of harmful chemicals can also go a long way. When possible, choose nontoxic cleaners and pesticides and opt for phosphate-free detergents.

- DON’T Use the Toilet as a Trash Can. Don’t flush tampons, baby wipes and other nonbiodegradable products. Also avoid flushing old prescription medications and take them to a prescription drug drop-off point instead.

- DON’T Use the Sink as a Trash Can. Never dump paint, oil or other household chemicals down the drain. This also goes for fat, oil and cooking grease. Instead, keep it in a jar under the sink and dispose of the jar in the garbage when it gets full.

Finally, if you see someone pouring oil down a storm drain or dumping waste in a stream, report them to the authorities. You may first want to try contacting your local government, but if that doesn’t work, you can contact your state environmental agency. The EPA also has an online form where you can report environmental violations.

Environmental Effects of Water Contamination

Environmental effects of water contamination include natural ecosystem harm and endangered wildlife. Marine life is especially at great risk of harm.

Marine animals suffer health problems, reduced lifespan and reproductive problems from water contamination. Excess nutrients from agricultural runoff create unnatural algae blooms in aquatic environments. Water contamination also reduces biodiversity, endangering the food supply for various marine animals.

Safe Drinking Water Act

The federal government regulates and protects our public drinking water via the Safe Drinking Water Act. The law, which was first enacted in 1974, covers water that comes from public sources, such as rivers, lakes, springs and groundwater wells. It does not cover private wells that provide water to fewer than 25 people.

The EPA sets national standards for drinking water that include maximum legal limits on more than 90 contaminants. The agency also requires water authorities to perform certain tests for contaminants to ensure the standards are achieved. And it dictates how contaminants should be removed.

States can set their own drinking water standards as long as their standards are at least as strict as the EPA’s requirements. The EPA and states can also take enforcement actions against water systems that violate safety standards.

52 Cited Research Articles

Consumernotice.org adheres to the highest ethical standards for content production and references only credible sources of information, including government reports, interviews with experts, highly regarded nonprofit organizations, peer-reviewed journals, court records and academic organizations. You can learn more about our dedication to relevance, accuracy and transparency by reading our editorial policy.

- White House. (2022, August 10). FACT SHEET: President Biden Signs the PACT Act and Delivers on His Promise to America’s Veterans. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/10/fact-sheet-president-biden-signs-the-pact-act-and-delivers-on-his-promise-to-americas-veterans/

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2022, March 7). Camp Lejeune water contamination health issues. Retrieved from https://www.va.gov/disability/eligibility/hazardous-materials-exposure/camp-lejeune-water-contamination/

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2020, July 29). Camp Lejeune, North Carolina: Public Health Activities. Retrieved from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/sites/lejeune/activities.html

- Pascus, B. (2019, May 7). New study claims 43 states expose millions to dangerous chemical in drinking water. Retrieved from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/drinking-water-may-contain-pfas-chemicals-in-43-states-according-to-new-study-by-environmental-working-group/

- Environmental Working Group. (2019, May 6). Mapping the PFAS Contamination Crisis: New Data Show 610 Sites in 43 States. Retrieved from https://www.ewg.org/release/mapping-pfas-contamination-crisis-new-data-show-610-sites-43-states

- Environmental Working Group. (2019, May 6). EWG Proposes PFAS Standards That Fully Protect Children’s Health. Retrieved from https://www.ewg.org/research/ewg-proposes-pfas-standards-fully-protect-children-s-health

- Kounang, N. (2019, April 30). Study estimates 15,000 cancer cases could stem from chemicals in California tap water. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2019/04/30/health/water-quality-cancer-risk-california-study/index.html

- Smith, M., Bosman, J. & Davey, M. (2019, April 25). Flint’s Water Crisis Started 5 Years Ago. It’s Not Over. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/25/us/flint-water-crisis.html?rref=collection%2Ftimestopic%2FWater%20Pollution&action=click&contentCollection=timestopics®ion=stream&module=stream_unit&version=latest&contentPlacement=4&pgtype=collection

- Turkewitz, J. (2019, February 22). Toxic ‘Forever Chemicals’ in Drinking Water Leave Military Families Reeling. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/22/us/military-water-toxic-chemicals.html?rref=collection%2Ftimestopic%2FWater%20Pollution&action=click&contentCollection=timestopics®ion=stream&module=stream_unit&version=latest&contentPlacement=3&pgtype=collection

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2019, February 13). Ground Water and Drinking Water: Drinking Water Health Advisories for PFOA and PFOS. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/drinking-water-health-advisories-pfoa-and-pfos

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2018, December 19). Ground Water and Drinking Water: Basic Information about Your Drinking Water. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/basic-information-about-your-drinking-water

- Natural Resources Defense Council. (2018, November 8). Flint Water Crisis: Everything You Need to Know. Retrieved from https://www.nrdc.org/stories/flint-water-crisis-everything-you-need-know

- Dewitt, K. (2018, August 21). Hoosick Falls Study Finds More Illnesses Linked to PFOA Exposure. Retrieved from https://www.wamc.org/new-york-news/2018-08-21/hoosick-falls-study-finds-more-illnesses-linked-to-pfoa-exposure

- Lyons, B. (2018, August 21). Survey: Higher rates of cancer, illnesses followed PFOA exposure. Retrieved from https://www.timesunion.com/news/article/Health-survey-finds-higher-rates-of-cancer-13169759.php

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2018, June 6). How EPA Regulates Drinking Water Contaminants. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/how-epa-regulates-drinking-water-contaminants

- Denchak, M. (2018, May 14). Water Pollution: Everything You Need to Know. Retrieved from https://www.nrdc.org/stories/water-pollution-everything-you-need-know#whatis

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2018, February 23). Potential Well Water Contaminants and Their Impacts. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/privatewells/potential-well-water-contaminants-and-their-impacts

- Agency of Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2018, January 10). What are the health effects? Retrieved from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas/health-effects.html

- Benedict, K. et al. (2017, November 10). Surveillance for Waterborne Disease Outbreaks Associated with Drinking Water — United States, 2013-2014. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6644a3.htm

- Weinmeyer, R. et al. (2017, October). The Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 and Its Role in Providing Access to Safe Drinking Water in the United States. Retrieved from https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/safe-drinking-water-act-1974-and-its-role-providing-access-safe-drinking-water-united-states/2017-10

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2017, September 1). Drinking Water Requirements for States and Public Water Systems: Drinking Water Regulations. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/dwreginfo/drinking-water-regulations

- Fries, A. (2017, June 19). Hoosick Falls residents shocked by high PFOA test results. Retrieved from https://www.timesunion.com/7dayarchive/article/Hoosick-Falls-meeting-11231034.php

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2017, January 12). Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sdwa

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2016, October). EPA Approved Laboratories for UCMR 3. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-10/documents/ucmr3-lab-approval.pdf

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2016, September 29). Contaminant Candidate List (CCL) and Regulatory Determination/Types of Drinking Water Contaminants. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/ccl/types-drinking-water-contaminants

- Sharma, S. & Bhattacharya, A. (2016, August 16). Drinking water contamination and treatment techniques. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13201-016-0455-7

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2016, May). Drinking Water Health Advisory for Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS). Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-05/documents/pfos_health_advisory_final-plain.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, February 18). Water. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/tips/water.htm

- Waldman, S. (2016, February 1). Schumer: Saint-Gobain needs to disclose full extent of Hoosick Falls pollution. Retrieved from https://www.politico.com/states/new-york/albany/story/2016/02/schumer-saint-gobain-needs-to-disclose-full-extent-of-hoosick-falls-pollution-030795

- Rich, N. (2016, January 6). The Lawyer Who Became DuPont’s Worst Nightmare. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/10/magazine/the-lawyer-who-became-duponts-worst-nightmare.html?module=inline

- Postman, A. (2016, January 5). 6 Ways You Can Help Keep Our Water Clean. Retrieved from https://www.nrdc.org/stories/6-ways-you-can-help-keep-our-water-clean

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015, July 1) Copper and Drinking Water from Private Wells. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/drinking/private/wells/disease/copper.html

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2014, February). Health Effects Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA). Retrieved from https://www.regulations.gov/document/EPA-HQ-OW-2014-0138-0002

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2014, February). Health Effects Document for Perfluorooctaine Sulfonate (PFOS). Retrieved from https://www.regulations.gov/document/EPA-HQ-OW-2014-0138-0003

- Dufar, A. et al. (2012, October). Animal Waste, Water Quality and Human Health. Retrieved from http://www.zaragoza.es/ciudad/medioambiente/onu/en/detallePer_Onu?id=487

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012, June 29). Drinking Water FAQ. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/drinking/public/drinking-water-faq.html

- World Health Organization. (2012, June). Pharmaceuticals in Drinking Water. Retrieved from http://www.zaragoza.es/ciudad/medioambiente/onu/en/detallePer_Onu?id=148

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009, April 10). Water Quality & Testing. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/drinking/public/water_quality.html

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2005, May). Home Water Testing. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-11/documents/2005_09_14_faq_fs_homewatertesting.pdf

- Arcadia Power. The Main Causes of Water Pollution in the U.S. Retrieved from https://blog.arcadia.com/main-causes-water-pollution-u-s/

- Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Getting Up to Speed: Ground Water Contamination. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-08/documents/mgwc-gwc1.pdf

- Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Health and Environmental Agencies of U.S. States and Territories. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/aboutepa/health-and-environmental-agencies-us-states-and-territories

- Environmental Protection Agency. EPA’s Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Action Plan. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2019-02/documents/pfas_action_plan_021319_508compliant_1.pdf

- Environmental Protection Agency. Ground and Drinking Water: National Primary Drinking Water Regulations. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/national-primary-drinking-water-regulations

- Environmental Protection Agency. Report Environmental Violations. Retrieved from https://echo.epa.gov/report-environmental-violations

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.(n.d.). Chapter 1: Introduction to agricultural water pollution. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/w2598e/w2598e04.htm

- Hurdle, J., Phillips, S. & Brady, J. EPA Says It Plans to Limit Toxic PFASS Chemicals, But Not Soon Enough For Critics. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2019/02/14/694660716/epa-says-it-will-regulate-toxic-pfas-chemicals-but-not-soon-enough-for-critics

- New York State Department of Health. Boil Water Notices — Frequently Asked Questions for Residents and Homeowners. Retrieved from https://www.health.ny.gov/environmental/water/drinking/boilwater/faq_residents_and_homeowners.htm

- State of Rhode Island Department of Health. (n.d.). PFAS Contamination of Water. Retrieved from http://www.health.ri.gov/water/about/pfas/

- Town of Simsbury Connecticut. (n.d.). Ten Things You Can Do To Reduce Water Pollution. Retrieved from https://www.simsbury-ct.gov/water-pollution-control/pages/ten-things-you-can-do-to-reduce-water-pollution

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (n.d.). PFAS — Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Retrieved from https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/pfas.asp

- United Nations. International Decade for Action ‘WATER FOR LIFE’ 2005-2015. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/quality.shtml

Calling this number connects you with a Consumer Notice, LLC representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Consumer Notice, LLC's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.

844-420-1914